Introduction

The Raspberry Pi has captured the imagination of hackers and makers alike. While it certainly wasn’t the first ARM development board on the market, its bargin basement price tag and the charitable philosophy of its inventors has sparked a huge interest in this little ARM system. What could be more appropriate for a new generation of programmers than a modern, safe and efficient programming language for their projects, Google Go.

This post describes the steps for installing Google Go from source on the Raspberry Pi. At the time of this post, trunk contains many improvements for ARM processors, including full support for cgo, which are not available in Go 1.0.x. It is expected that these enhancements will be available when Go 1.1 ships next year. If you are reading this post in September 2013, then it’s likely you will want to use the version of Go shipping with your operating system distribution rather than these instructions.

Update May, 2013 If you want to save yourself some time, precompiled binary releases of Go 1.1 for linux/arm are available. Please see the Unofficial ARM tarballs link at the top of the page.

Setting up your Pi

Before you compile Go on your Pi you should follow these steps to ensure a successful compilation. Briefly summarised, they are:

- Install Raspbian

- Configure your memory split

- Add some swap

Install Raspbian

The downloads page on the Raspberry Pi website contains links to SD card images for various Linux distributions. This tutorial recommends the Raspbian wheezy flavour of Debian. Follow the instructions for creating an SD card image and continue to the next step once you have ssh’d into your Raspbian installation.

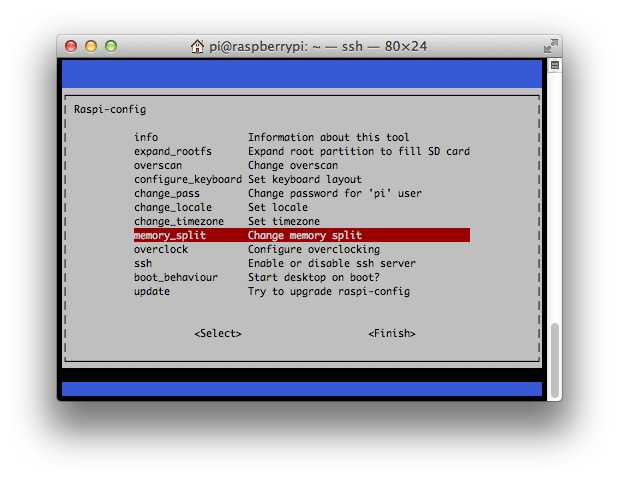

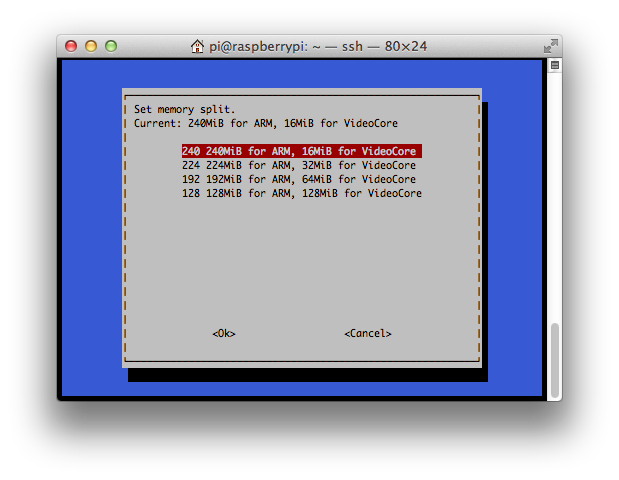

Configure your memory split

The Pi comes with 256mb of memory which is shared between the video subsystem and the main processor. Compiling and linking Go programs can consume over 100mb of ram so it is recommended that the memory split be adjusted in favor of the main processor, at least while working with Go code. The Raspbian distribution makes this very easy with the raspi-config utility

% sudo raspi-config

Then reboot your system

% sudo shutdown -r now

Add some swap

To run the full test suite you will need some swap. This can be accomplished a variety of ways, using an external USB hard drive, or swapping over NFS. I’ll describe how to setup a NFS swap partition as this is the configuration I am using to generate this tutorial.

% sudo dd if=/dev/zero of=/import/nas/swap bs=1024 count=1048576 1048576+0 records in

1048576+0 records out

1073741824 bytes (1.1 GB) copied, 136.045 s, 7.9 MB/s

% sudo losetup /dev/loop0 /import/nas/swap

% sudo mkswap /dev/loop0

Setting up swapspace version 1, size = 1048572 KiB no label, UUID=7ba9443d-c64c-416f-9931-39e3e2decf0f

% sudo swapon /dev/loop0

% free -m

total used free shared buffers cached

Mem: 232 78 153 0 0 24

-/+ buffers/cache: 52 179

Swap: 1123 15 1108

Installing the prerequisites

Raspbian comes with almost all the tools you need to compile Go already installed, but to be sure you should install the following packages, described on the golang.org website.

% sudo apt-get install -y mercurial gcc libc6-dev

Cloning the source

% hg clone -u default https://code.google.com/p/go $HOME/go warning: code.google.com certificate with fingerprint 9f:af:b9:ce:b5:10:97:c0:5d:16:90:11:63:78:fa:2f:37:f4:96:79 not verified (check hostfingerprints or web.cacerts config setting)

destination directory: go

requesting all changes

adding changesets

adding manifests

adding file changes

added 14430 changesets with 52478 changes to 7406 files (+5 heads) updating to branch default

3520 files updated, 0 files merged, 0 files removed, 0 files unresolved

Building Go

% cd $HOME/go/src % ./all.bash

If all goes well, after about 90 minutes you should see

ALL TESTS PASSED --- Installed Go for linux/arm in /home/dfc/go Installed commands in /home/dfc/go/bin

If there was an error relating to out of memory, or you couldn’t configure an appropriate swap device, you can skip the test suite by executing

% cd $HOME/go % ./make.bash

as an alternative to ./all.bash.

Adding the go command to your path

The go command should be added to your $PATH

% export PATH=$PATH:$HOME/go/bin

% go version

go version devel +cfbcf8176d26 Tue Sep 25 17:06:39 2012 +1000

Now, Go and make something awesome.

Additional resources

- Installation instructions for building Go from source (golang.org)

- Raspbian ARM hard-float distribution (www.raspbian.org)

- GoArm page on the Go Language Community Wiki (code.google.com/p/go-wiki)

- OpenVG on the Raspberry Pi (mindchunk.blogspot.com.au)

- Go bindings for the OpenVG 2D vector API (github.com/ajstarks/openvg)

- The amazing GoSpeccy Spectrum emulator fully supports the Pi (github.com/remogatto/gospeccy)