A few months ago I introduced gb as a proof of concept to the audience at GDG Berlin. Since then, together with a small band of contributors and an enthusiastic cabal of early adopters, gb has moved from proof of concept, written mostly on trains during a trip through Europe, to something approaching a usable build tool.

This post gives an introduction to gb, and explains the benefits of adopting a project based workflow for building solutions in Go. If you want to read more about the motivations for gb, please read the previous post in this series.

gb

gb is a project based build tool for the Go programming language.

gb projects define an on disk layout that permits repeatable builds via source vendoring. When vendoring (copying) code into a gb project, the original source is not rewritten or modified.

As gb is written in Go, its packages can be used to create plugins to gb that extend its functionality.

Why is a project based approach useful ?

Why is a project based approach, as opposed to a workspace based approach like $GOPATH, useful ?

First and foremost, by structuring your Go application as a project, rather than a piece of a distributed global workspace, you gain control over all the source that goes into your application, including that of its dependencies.

Second, while your project’s layout contains both the code that you have written, and the code that your code depends on, there is a clear separation between the two; they live in different subdirectory trees.

Thirdly, now your project, and by extension the repository that houses it, contains all the source to build your application, having multiple working copies on disk is trivial. If you are part of a team responsible for maintaining multiple releases, this is a very useful property.

Lastly. As your project can be built at any time without going out to the internet to fetch code, you are insulated from political, financial, or technical events that can unexpectedly break your build. Conversely, as the dependencies for your project are included with the project, upgrading those dependencies is atomic and affects everyone on the team automatically without them having to run external steps like go get -u or godeps -u dependencies.txt.

How is gb different ?

In the previous section I outlined the advantages I see in using a project based tool to build Go applications. I want to digress for a moment to explain why gb is different to other existing go build tools.

gb is not a wrapper around the go tool. Not wrapping the go tool means gb is not constrained to solutions that can be implemented with $GOPATH tricks. Not relying on the go tool means gb can ship faster, and fix bugs faster than the fixed pace of releases of the Go toolchain.

You can read more about the rationale for gb here, and reasons for not wrapping the go tool here.

Being a project owner

In the discussions I’ve had about gb, I’ve tried to emphasise the role of the project owner. The owner of the project has a special responsibility; they are responsible for admitting new dependencies into a project, and for curating those dependencies once they are part of the shipping product.

Whether the role of project owner falls to a single engineer, or is distributed across your whole team, it is the project owner who is ultimately responsible for shipping your product, so gb gives you the tools to achieve this without having to rely on a third party.

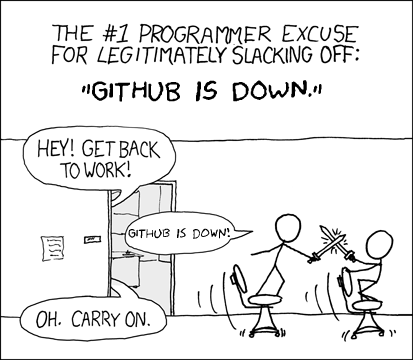

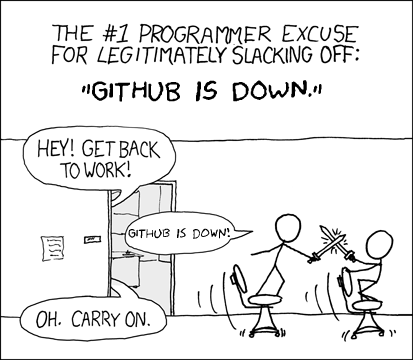

Project ownership is important. You, the developer, the project owner, the build engineer, needs to own all the source that goes into your product whether you wrote it or not. Don’t be the person who cannot deliver a release because GitHub is down.

No import rewriting

gb is built around a philosophy of leaving the source of a project’s dependency untouched.

The are various technical reasons why I believe import rewriting is a bad idea for Go projects, I won’t repeat them here.

It is my hope that maybe one day, build tools like gb can get a bit smarter about managing dependencies, and avoid the need for whole cloth vendoring, but this cannot happen if imports are rewritten.

Demo time

Enough background, let’s show off gb.

Creating a gb project

Creating a gb project is as simple as creating a directory. This directory can be anywhere of your choosing; it does not need to be inside $GOPATH, in fact gb does not use $GOPATH.

% mkdir -p demo/src

% cd demo

demo is now a gb project. A gb project is defined as any directory that contains a directory called src/. We’ll refer to the root of the project, demo in this case, as the project root, or $PROJECT for short. Let’s go ahead and create a single main package.

% mkdir -p src/cmd/helloworld

% cat > src/cmd/helloworld/main.go <<EOF

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

fmt.Println("Hello world from gb")

}

EOF

Commands (main packages) don’t have to be placed in src/cmd/, but that is a nice tradition that has emerged from the Go standard library, so we’ll follow it here. Also note that although gb does not use the go tool to compile Go code, that code must still be structured into packages.

In fact gb is much stricter in this respect, Go code can only be built if it is inside a package, there are no facilities to build or run a single .go source file.

gb supports all the usual ways of compiling one package by passing the name of the package to gb build, but it is simpler to just build the entire project by staying at the root of your project and issuing gb build to build all the source in your project.

gb has support for incremental compilation, so even though gb build is told to build all the source in the project, it will only recompile the parts that have changed; there is no need to point them out to the compiler. Also note that there is no gb install command. gb build both builds and installs (caches packages forincremental compilation later).

With all this said, let’s go ahead an build this project, then run the resulting program

% gb build

cmd/helloworld

% bin/helloworld

Hello world from gb

By default gb prints out the names of packages it is compiling, you can use the -q flag if you want to suppress this output. When compiling, packages will be built and placed in $PROJECT/pkg/ for possible reuse by latter compilation cycles, main packages (commands), will be placed in $PROJECT/bin/.

If this project contained multiple commands, they would all be built and placed in $PROJECT/bin/. To demonstrated this I created a few more main packages in this project, let’s compile them and look at the result

% gb build

cmd/client

cmd/helloworld

cmd/server

% ls bin/

client helloworld server

gb project layout

The previous section walked through the creation of a gb project from scratch and showed using gb build to compile the project.

Let’s have a look at the directory tree of this project an add some annotations to reinforce the gb project concepts.

% tree $(pwd)

/home/dfc/demo

├── bin

│ ├── client

│ ├── helloworld

│ └── server

└── src

└── cmd

├── client

│ └── main.go

├── helloworld

│ └── main.go

└── server

└── main.go

6 directories, 6 files

Starting from the top, we have a bin/ directory, this is created by gb build when building main packages to hold the final output of linking executable programs. Inside bin/ we have the the binaries that were built.

Next is the src/ which contains the subdirectory cmd/ and inside that, three packages, client, helloworld, and server.

The final directories you will find inside a gb project is $PROJECT/pkg/ for compiled go packages, and $PROJECT/vendor/ for the source of your project’s dependencies. We’ll discuss vendoring dependencies later in this piece.

Source control

gb doesn’t care about source control, all it cares about is the source of your project is arranged in the format it expects. How those files got there, or who is responsible for tracking changes to them is outside gb’s concern.

Of course, source control is a great idea, and you should be tracking the source of your project using source control. Let’s create a git repo in the $PROJECT root now

% git init .

Initialized empty Git repository in /home/dfc/demo/.git/

% git add src/

% git commit -am 'initial import'

[master (root-commit) aa1acfd] initial import

3 files changed, 21 insertions(+)

create mode 100644 src/cmd/client/main.go

create mode 100644 src/cmd/helloworld/main.go

create mode 100644 src/cmd/server/main.go

Then of course add a git remote and push to it.

You should not place $PROJECT/bin/ or $PROJECT/pkg/ under source control, as they are temporary directories. You may wish to add a .gitignore or similar to prevent doing so accidentally.

Dependency management

A project which doesn’t have any dependencies, apart from the standard library, is not going to be very a compelling use case for gb. For this next section I’ll walk through creating a new gb project which has several dependencies.

The source for this project is online at github.com/constabulary/example-gsftp. Let’s start by creating the project structure and adding some source

% mkdir example-gsftp

% cd example-gsftp

% mkdir -p src/cmd/gsftp # this is our main package

% vim src/cmd/gsftp/main.go

The source for cmd/gsftp/main.go is too long to include, but is available here.

This project depends on golang.org/x/crypto/ssh package and github.com/pkg/sftp package, which itself has a dependency on github.com/kr/fs. In its current state, if you were to gb build this project it would fail with an error like this

% gb build

FATAL command "build" failed: failed to resolve import path "cmd/gsftp": cannot find package "github.com/pkg/sftp" in any of:

/home/dfc/go/src/github.com/pkg/sftp (from $GOROOT)

/home/dfc/example-gsftp/src/github.com/pkg/sftp (from $GOPATH)

/home/dfc/example-gsftp/vendor/src/github.com/pkg/sftp

gb is unable to find the a package with an import path of github.com/pkg/sftp, in either the project’s source directory, $PROJECT/src/, or the project’s vendored source directory, $PROJECT/vendor/src/.

note the references to $GOPATH are a side effect of reusing the go/build package. gb does not use $GOPATH, this message will be addressed in the future.

Now, I have copies of all of the source of these packages in my $GOPATH, so I can copy them into the $PROJECT/vendor/src directory by hand to satisfy the build.

% mkdir -p vendor/src/github.com/pkg/sftp

% cp -r $GOPATH/src/github.com/pkg/sftp/* vendor/src/github.com/pkg/sftp

% mkdir -p vendor/src/github.com/kr/fs

% cp -r $GOPATH/src/github.com/kr/fs/* vendor/src/github.com/kr/fs

% mkdir -p vendor/src/golang.org/x/crypto/ssh

% cp -r $GOPATH/src/golang.org/x/crypto/ssh/* vendor/src/golang.org/x/crypto/ssh

% gb build

github.com/kr/fs

golang.org/x/crypto/ssh

golang.org/x/crypto/ssh/agent

github.com/pkg/sftp

cmd/gsftp

% ls -l bin/gsftp

-rwxrwxr-x 1 dfc dfc 5949744 Jun 8 14:05 bin/gsftp

For completeness’s sake, let’s take a look at the directory structure of the project with these vendored dependencies.

% tree -d $(pwd)

/home/dfc/example-gsftp

├── bin

├── pkg

│ └── linux

│ └── amd64

│ ├── github.com

│ │ ├── kr

│ │ └── pkg

│ └── golang.org

│ └── x

│ └── crypto

│ └── ssh

├── src

│ └── cmd

│ └── gsftp

└── vendor

└── src

├── github.com

│ ├── kr

│ │ └── fs

│ └── pkg

│ └── sftp

│ └── examples

│ ├── buffered-read-benchmark

│ ├── buffered-write-benchmark

│ ├── streaming-read-benchmark

│ └── streaming-write-benchmark

└── golang.org

└── x

└── crypto

└── ssh

├── agent

├── terminal

├── test

└── testdata

34 directories

Using the gb-vendor plugin

gb’s answer to dependency management is vendoring, copying the source of your project’s dependencies into $PROJECT/vendor/src/. As you saw above, this process can be quite tedious, especially if you do not have the source of the dependency easily to hand.

To assist with this process, gb ships with a plugin called gb-vendor, which aims to automate a lot of this work.

gb-vendor can fetch the dependencies of your project. Let’s use it to automate the steps we just did above.

% rm -rf vendor/src

% gb vendor fetch github.com/pkg/sftp

% gb vendor fetch github.com/kr/fs

% gb vendor fetch golang.org/x/crypto/ssh

% gb build

github.com/kr/fs

golang.org/x/crypto/ssh

golang.org/x/crypto/ssh/agent

github.com/pkg/sftp

cmd/gsftp

At this point it is a good idea to add your project’s vendor/ directory to source control.

% git add vendor/

% git commit -am 'added vendored dependencies'

gb-vendor also provides commands to update, delete, and report on the vendor dependencies of a project. For example

% gb vendor update github.com/pkg/sftp

will replace the source of github.com/pkg/sftp with the latest available upstream.

% gb vendor delete github.com/pkg/kr/fs

Will remove $PROJECT/vendor/src/github.com/pkg/kr/fs from disk, and remove its entry from the manifest file.

Lastly, the list subcommand behaves similarly to go list and lets you report on the dependencies recorded in the manifest file.

% gb vendor list

github.com/pkg/sftp https://github.com/pkg/sftp master f234c3c6540c0358b1802f7fd90c0879af9232eb

github.com/kr/fs https://github.com/kr/fs master 2788f0dbd16903de03cb8186e5c7d97b69ad387b

golang.org/x/crypto/ssh https://go.googlesource.com/crypto/ssh master c10c31b5e94b6f7a0283272dc2bb27163dcea24b

gb-vendor is completely optional

At this point you’re probably saying, “Hang on, aren’t you the person who made a big song and dance about no metadata files ?”.

Yes, it is true that gb-vendor records the dependencies it fetches in a manifest file, ($PROJECT/vendor/manifest), but this manifest file is only used by gb-vendor, and is not part of gb.

gb-vendor is a plugin, it adds a little bit of smarts on top of git clone, or hg checkout, but it isn’t mandatory to use gb-vendor to build gb projects.

All gb cares about is the source on disk, you don’t have to use it. If your workflow works well with svn externals or git subtrees, or maybe just copying the package and recording the revision you copied in the commit message, you can use that approach as well.

gb-vendor is not required to use gb, and gb is completely oblivious to its operation. All that gb cares about is finding the source on disk with the correct layout. You are free to use any method of managing the contents of your $PROJET/vendor/src directory.

How does gb handle the diamond dependency problem ?

In every Go program, regardless of which tool built it (gb, the go tool, Makefile, or by hand), there may only be one copy of a package linked into the final binary.

For project owners this means that if they encounter a situation where two dependencies of their project expect different exported API’s of a third package, they must resolve this problem at the point they introduce these dependencies into their project.

Resolving a diamond dependency conflict requires the project owner choose which copy (Go packages do not have a notion of versions) of the source of that third dependency they will place in $PROJECT/vendor/src/ and adjusting, updating, or replacing other dependencies as required.

Can a gb project be a library ?

In the presentations I’ve made about gb, I have focussed on development teams shipping products written in Go. I see these teams as the ones who have the most to gain, and the least to lose, from adopting gb, so it is reasonable to focus on those teams first.

You can also use gb to build libraries (effectively gb projects that don’t have main packages), and then vendor the source of that project’s src/ directory into another gb project as demonstrated above.

At the moment no automated tools exist to assist with this process, but it is likely that gb-vendor will acquire this ability if there is significant demand in developing libraries in the gb project format.

Wrapping up

This post has described the theory and the practice of using gb. I hope that you have found it useful, and in turn that you may find gb useful if you are part of a team charged with delivering solutions using Go.

getgb.io

- Project based workflow

- Repeatable builds via source vendoring without import rewriting

- Reusable components with a plugin interface