This blog post was inspired by a conversation with a co-worker about using a slice as a stack. The conversation turned into a wider discussion on the way slices work in Go, so I thought it would be useful to write it up.

Arrays

Every discussion of Go’s slice type starts by talking about something that isn’t a slice, namely, Go’s array type. Arrays in Go have two relevant properties:

- They have a fixed size;

[5]int is both an array of 5 ints and is distinct from [3]int.

- They are value types. Consider this example:

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

var a [5]int

b := a

b[2] = 7

fmt.Println(a, b) // prints [0 0 0 0 0] [0 0 7 0 0]

}

The statement b := a declares a new variable, b, of type [5]int, and copies the contents of a to b. Updating b has no effect on the contents of a because a and b are independent values.

Slices

Go’s slice type differs from its array counterpart in two important ways:

- Slices do not have a fixed length. A slice’s length is not declared as part of its type, rather it is held within the slice itself and is recoverable with the built-in function

len.

- Assigning one slice variable to another does not make a copy of the slices contents. This is because a slice does not directly hold its contents. Instead a slice holds a pointer to its underlying array which holds the contents of the slice.

As a result of the second property, two slices can share the same underlying array. Consider these examples:

- Slicing a slice:

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

var a = []int{1,2,3,4,5}

b := a[2:]

b[0] = 0

fmt.Println(a, b) // prints [1 2 0 4 5] [0 4 5]

}

In this example a and b share the same underlying array–even though b starts at a different offset in that array, and has a different length. Changes to the underlying array via b are thus visible to a.

- Passing a slice to a function:

package main

import "fmt"

func negate(s []int) {

for i := range s {

s[i] = -s[i]

}

}

func main() {

var a = []int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

negate(a)

fmt.Println(a) // prints [-1 -2 -3 -4 -5]

}

In this example a is passed to negateas the formal parameter s. negate iterates over the elements of s, negating their sign. Even though negate does not return a value, or have any way to access the declaration of a in main, the contents of a are modified when passed to negate.

Most programmers have an intuitive understanding of how a Go slice’s underlying array works because it matches how array-like concepts in other languages tend to work. For example, here’s the first example of this section rewritten in Python:

Python 2.7.10 (default, Feb 7 2017, 00:08:15)

[GCC 4.2.1 Compatible Apple LLVM 8.0.0 (clang-800.0.34)] on darwin

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> a = [1,2,3,4,5]

>>> b = a

>>> b[2] = 0

>>> a

[1, 2, 0, 4, 5]

And also in Ruby:

irb(main):001:0> a = [1,2,3,4,5]

=> [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

irb(main):002:0> b = a

=> [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

irb(main):003:0> b[2] = 0

=> 0

irb(main):004:0> a

=> [1, 2, 0, 4, 5]

The same applies to most languages that treat arrays as objects or reference types.

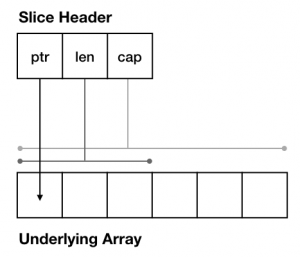

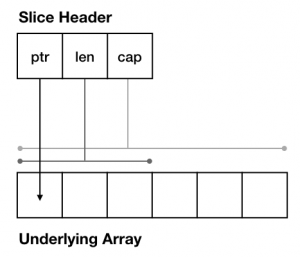

The slice header value

The magic that makes a slice behave both as a value and a pointer is to understand that a slice is actually a struct type. This is commonly referred to as a slice header after its counterpart in the reflect package. The definition of a slice header looks something like this:

package runtime

type slice struct {

ptr unsafe.Pointer

len int

cap int

}

This is important because unlike map and chan types slices are value types and are copied when assigned or passed as arguments to functions.

To illustrate this, programmers instinctively understand that square‘s formal parameter v is an independent copy of the v declared in main.

package main

import "fmt"

func square(v int) {

v = v * v

}

func main() {

v := 3

square(v)

fmt.Println(v) // prints 3, not 9

}

So the operation of square on its v has no effect on main‘s v. So too the formal parameter s of double is an independent copy of the slice s declared in main, not a pointer to main‘s s value.

package main

import "fmt"

func double(s []int) {

s = append(s, s...)

}

func main() {

s := []int{1, 2, 3}

double(s)

fmt.Println(s, len(s)) // prints [1 2 3] 3

}

The slightly unusual nature of a Go slice variable is it’s passed around as a value, not than a pointer. 90% of the time when you declare a struct in Go, you will pass around a pointer to values of that struct. This is quite uncommon, the only other example of passing a struct around as a value I can think of off hand is time.Time.

It is this exceptional behaviour of slices as values, rather than pointers to values, that can confuses Go programmer’s understanding of how slices work. Just remember that any time you assign, subslice, or pass or return, a slice, you’re making a copy of the three fields in the slice header; the pointer to the underlying array, and the current length and capacity.

Putting it all together

I’m going to conclude this post on the example of a slice as a stack that I opened this post with:

package main

import "fmt"

func f(s []string, level int) {

if level > 5 {

return

}

s = append(s, fmt.Sprint(level))

f(s, level+1)

fmt.Println("level:", level, "slice:", s)

}

func main() {

f(nil, 0)

}

Starting from main we pass a nil slice into f as level 0. Inside f we append to s the current level before incrementing level and recursing. Once level exceeds 5, the calls to f return, printing their current level and the contents of their copy of s.

level: 5 slice: [0 1 2 3 4 5]

level: 4 slice: [0 1 2 3 4]

level: 3 slice: [0 1 2 3]

level: 2 slice: [0 1 2]

level: 1 slice: [0 1]

level: 0 slice: [0]

You can see that at each level the value of s was unaffected by the operation of other callers of f, and that while four underlying arrays were created higher levels of f in the call stack are unaffected by the copy and reallocation of new underlying arrays as a by-product of append.

Further reading

If you want to find out more about how slices work in Go, I recommend these posts from the Go blog:

Notes