This is an article about compiler directives; or as they are commonly known, pragmas. It’s derived from a talk of a similar name that I gave last year at GopherChina in Shanghai.

But first, a history lesson

Before we talk about Go, let’s talk a little about pragmas, and their history. Many languages have the notion of an attribute, or directive, that changes the way source code is interpreted during compilation. For example, Perl has the use function:

use strict; use strict "vars"; use strict "refs"; use strict "subs";

use enable features, or makes the compiler interpret the source of the program differently, by making the compiler more pedantic or enabling a new syntax mode.

Javascript has something similar. ECMAScript 5 extended the language with optional modes, such as:

"use strict";

When the Javascript interpreter comes across the words "use strict"; it enables, so called, Strict Mode when parsing your Javascript source. 1

Rust is similar, it uses the attributes syntax to enable unstable features in the compiler or standard library.

#[inline(always)]

fn super_fast_fn() { ... }

#[cfg(target_os = "macos")]

mod macos_only { ... }

The inline(always) attribute tells the compiler that it must inline super_fast_fn. The target_os attribute tells the compiler to only compile the macos_only module on OS X.

The name pragma comes from ALGOL 68, where they were called pragmats, which was itself shorthand for the word pragmatic. When they were adopted by C in the 1970’s, the name was shortened again to #pragma, and due to the widespread use of C, became fully integrated into the programmer zeitgeist.

#pragma pack(2)

struct T {

int i;

short j;

double k;

};

This example says to the compiler that the structure should be packed on a two byte boundary; so the double, k, will start at an offset of 6 bytes from the address of T, not the usual 8.

C’s #pragma directive spawned a host of compiler specific extensions, like gcc’s __builtin directive.

Does Go have pragmas?

Now that we know a little bit of the history of pragmas, maybe we can now ask the question, does Go have pragmas?

You saw earlier that #pragma, like #include and #define are implemented in C style languages with a preprocessor, but Go does not have a preprocessor, or macros, so, the question remains, does Go have pragmas?

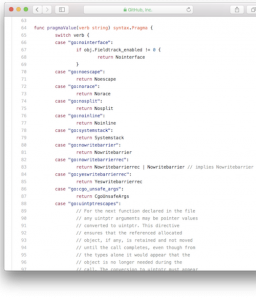

It turns out that, yes, even though Go does not have macros, or a preprocessor, Go does indeed support pragmas. They are implemented by the compiler as comments.

Just to drive home the point, they’re actually called pragmas in the source of the Go compiler.

So, clearly the name pragma, along with the idea, isn’t going away.

This article focuses on a only a few of the pragmas that the compiler recognises, partly because the list changes frequently, but mostly because not all of them are usable by you as programmers.

Here are some examples to whet your appetite

//go:noescape func gettimeofday(tv *Timeval) (err Errno)

This is an example of the noescape directive on the gettimeofday stub from the syscall package.

//go:noinline

func lshNop1(x uint64) uint64 {

// two outer shifts should be removed

return (((x << 5) >> 2) << 2)

}

This is an example of the noinline directive from a test fixture in the compiler tests.

//go:nosplit

func atomicstorep(ptr unsafe.Pointer, new unsafe.Pointer) {

writebarrierptr_prewrite((*uintptr)(ptr), uintptr(new))

atomic.StorepNoWB(noescape(ptr), new)

}

This is an example of the nosplit directive inside the runtime’s atomic support functions.

Don’t worry if this was all a bit quick, we’re going to explore these examples, and more, during the remainder of this article.

A word of caution ?

Before I continue, I want to offer a word of caution.

Pragmas are not part of the language. They might be implemented the gc compiler, but you will not find them in the spec. At a higher level, the idea of adding pragmas to the language caused considerable debate, especially after the first few established a precedent. In a debate about adding the //go:noinline directive Rob Pike opined,

“Useful” is always true for a feature request. The question is, does the usefulness justify the cost? The cost here is continued proliferation of magic comments, which are becoming too numerous already.

–Rob Pike

I’ll leave you to decide if adding pragmas to Go was a good idea or not.

As I mentioned earlier pragma directives are placed in Go comments with a precise syntax. The syntax has the general form:

//go:directive

The go: prefix can be replaced with another, so you can see that the Go team were at least considering future growth, even though they don’t encourage it. It’s also important to note that there is no space between the // and the go keyword. This is partly an accident of history, but it also makes it less likely to conflict with a regular comment.

Lastly, some of these directives require you to do one or more of the following:

- import the

unsafepackage. - compile with the undocumented

-+flag. - be part of the

runtimepackage.

If you get it wrong, your directive might be ignored, and in most cases you code will compile but might be slower or behave incorrectly.

//go:noescape

Enough with the preflight safety checks.

Early in Go’s life, the parts that went into a complete Go program would include Go code (obviously), some C code from the runtime, and some assembly code, again from the runtime or syscall package. The take away is it was expected that inside a package, you’d occasionally find functions which were not implemented in Go.

Now, normally this mixing of languages wouldn’t be a problem, except when it interacts with escape analysis. In Go it’s very common to do something like this,

func NewBook() (*Book) {

b := Book{ Mice: 12, Men: 9 }

return &b

}

That is, inside NewBook we declare and initialise a new Book variable b, then return the address of b. We do this so often inside Go it probably doesn’t sink in that if you were to do something like this in C, the result would be pernicious memory corruption as the address returned from NewBook would point to the location on the stack where b was temporarily allocated.

Escape analysis

Escape analysis identifies variables whose lifetimes will live beyond the lifetime of the function in which it is declared, and moves the location where the variable is allocated from the stack to the heap. Technically we say that b escapes to the heap.

Obviously there is a cost; heap allocated variables have to be garbage collected when they are no longer reachable, stack allocated variables are automatically free’d when their function returns. Keep that in mind.

func BuildLibrary() {

b := Book{Mice: 99: Men: 3}

AddToCollection(&b)

}

Now, lets consider a slightly different version of what we saw above. In this contrived example, BuildLibrary declares a new Book, b, and passes the address of b to AddToCollection. The question is, “does b escape to the heap?”

The answer is, it depends. It depends on what AddToCollection does with the *Book passed to it. If AddToCollection did something like this,

func AddToCollection(b *Book) {

b.Classification = "fiction"

}

then that’s fine. AddToCollection can address those fields in Book irrespective of if b points to an address on the stack or on the heap. Escape analysis would conclude that the b declared in BuildLibrary did not escape, because AddToCollection did not retain a copy of the *Book passed to it, and can therefore be allocated cheaply on the stack.

However, if AddToCollection did something like this,

var AvailableForLoan []*Book

func AddToCollection(b *Book) {

AvailableForLoan = append(AvailableForLoan, b)

}

that is, keep a copy of b in some long lived slice, then that will have an impact on the b declared in BuildLibrary. b must be allocated on the heap so that it lives beyond the lifetime of AddToCollection and BuildLibrary. Escape analysis has to know what AddToCollection does, what functions it calls, and so on, to know if a value should be heap or stack allocated. This is the essence of escape analysis.

os.File.Read

That was a lot of background, let’s get back to the //go:noescape pragma. Now we know that the call stack of functions affects whether a value escapes or not, consider this very common situation (error handling elided for brevity),

f, _ := os.Open("/tmp/foo")

buf := make([]byte, 4096)

n, _ := f.Read(buf)

We open a file, make a buffer, and we read into that buffer. Is buf allocated on the stack, or on the heap?

As we saw above, it depends on what happens inside os.File.Read. os.File.Read calls down through a few layers to syscall.Read, and this is where it gets complicated. syscall.Read calls down into syscall.Syscall to do the operating system call. syscall.Syscall is implemented in assembly. Because syscall.Syscall is implemented in assembly, the compiler, which works on Go code, cannot “see” into that function, so it cannot see if the values passed to syscall.Syscall escape or not. Because the compiler cannot know if the value might escape, it must assume it will escape.

This was the situation in issue 4099. If you wanted to write a small bit of glue code in assembly, like the bytes, md5, or syscall package, anything you passed to it would be forced to allocated on the heap even if you knew that it doesn’t.

package bytes //go:noescape // IndexByte returns the index of the first instance of c in s, // or -1 if c is not present in s. func IndexByte(s []byte, c byte) int // ../runtime/asm_$GOARCH.s

So this is precisely what the //go:noescape pragma does. It says to the compiler, “the next function declaration you see, assume that none of the arguments escape.” We’ve said to the compiler; trust us, IndexByte and its children do not keep a reference to the byte slice.

In this example from Go 1.5 you can see that bytes.IndexByte is implemented in assembly 2. By marking this function //go:noescape, it will avoid stack allocated []byte slices escaping to the heap unnecessarily.

Can you use //go:noescape in your code?

Can you use //go:noescape in your own code? Yes, but it can only be used on the forward declarations.

package main

import "fmt"

//go:noescape

func length(s string) int // implemented in an .s file

func main() {

s := "hello world"

l := length(s)

fmt.Println(l)

}

Note, you’re bypassing the checks of the compiler, if you get this wrong you’ll corrupt memory and no tool will be able to spot this.

//go:norace

Forking in a multithreaded program is complicated. The child process gets a complete, independent, copy of the parent’s memory, so things like locks, implemented as values in memory can become corrupt when suddenly two copies of the same program see locks in different state.

Fork/exec in the Go runtime is handled with care by the syscall package which coordinates to make sure that the runtime is in quiescent state during the brief fork period. However, when the race runtime is in effect, this becomes harder.

To spot races, when compiling in race mode, the program is rewritten so every read and write goes via the race detector framework to detect unsafe memory access. I’ll let the commit explain.

// TODO(rsc): Remove. Put //go:norace on forkAndExecInChild instead.

func isforkfunc(fn *Node) bool {

// Special case for syscall.forkAndExecInChild.

// In the child, this function must not acquire any locks, because

// they might have been locked at the time of the fork. This means

// no rescheduling, no malloc calls, and no new stack segments.

// Race instrumentation does all of the above.

return myimportpath != "" && myimportpath == "syscall" &&

fn.Func.Nname.Sym.Name == "forkAndExecInChild"

}

As Russ’s comment shows above, the special casing in the compiler was removed in favour of a directive on the syscall.forkAndExecInChild functions in the syscall package.

// Fork, dup fd onto 0..len(fd), and exec(argv0, argvv, envv) in child.

// If a dup or exec fails, write the errno error to pipe.

// (Pipe is close-on-exec so if exec succeeds, it will be closed.)

// In the child, this function must not acquire any locks, because

// they might have been locked at the time of the fork. This means

// no rescheduling, no malloc calls, and no new stack segments.

// For the same reason compiler does not race instrument it.

// The calls to RawSyscall are okay because they are assembly

// functions that do not grow the stack.

//go:norace

func forkAndExecInChild(argv0 *byte, argv, envv []*byte, chroot, dir

*byte, attr *ProcAttr, sys *SysProcAttr, pipe int)

(pid int, err Errno) {

This was replaced by the annotation //go:norace by Ian Lance Taylor in Go 1.6, which removed the special case in the compiler, however //go:norace is still only used in one place in the standard library.

Should you use //go:norace in your own code?

Should you use //go:norace in your own code? Using //go:norace will instruct the compiler to not annotate the function, thus will not detect any data races if they exist. This program contains a data race, which will not be reported by the race detector because of the //go:norace annotation.

package main

var v int

//go:norace

func add() {

v++

}

func main() {

for i := 0; i < 5; i++ {

go add()

}

}

Given the race detector has no known false positives, there should be very little reason to exclude a function from its scope.

//go:nosplit

Hopefully by now everyone knows that a goroutine’s stack is not a static allocation. Instead each goroutine starts with a few kilobytes of stack and, if necessary, will grow.

The technique that the runtime uses to manage a goroutine’s stack relies on each goroutine keeping track of its current stack usage. During the function preamble, a check is made to ensure there is enough stack space for the function to run. If not, the code traps into the runtime to grow the current stack allocation.

"".fn t=1 size=120 args=0x0 locals=0x80

0x0000 00000 (main.go:5) TEXT "".fn(SB), $128-0

0x0000 00000 (main.go:5) MOVQ (TLS), CX

0x0009 00009 (main.go:5) CMPQ SP, 16(CX)

0x000d 00013 (main.go:5) JLS 113

Now, this preamble is quite small, as we see it’s only a few instructions on x86.

- A load from an offset of the current

gregister, which holds a pointer to the current goroutine. - A compare against the stack usage for this function, which is a constant known at compile time.

- And a branch to the slow path, which is rare and easily predictable.

But sometimes even this overhead is unacceptable, and occasionally, unsafe, if you’re the runtime package itself. So a mechanism exists, via an annotation in the compiled form of the function to skip the stack check preamble. It should also be noted that the stack check is inserted by the linker, not the compiler, so it applies to assembly functions and, while they existed, C functions.

Up until Go 1.4, the runtime was implemented in a mix of Go, C and assembly.

// All reads and writes of g's status go through readgstatus, casgstatus

// castogscanstatus, casfromgscanstatus.

#pragma textflag NOSPLIT

uint32

runtime·readgstatus(G *gp)

{

return runtime·atomicload(&gp->atomicstatus);

}

In this example, runtime.readgstatus, we can see the C style #pragma textflag NOSPLIT. 3

When the runtime was rewritten in Go, a way to say that a particular function should not have the stack split check was still required. This was often needed as taking a stack split inside the runtime was forbidden because a stack split implicitly needs to allocate memory, which would lead to recursive behaviour. Hence #pragma textflag NOSPLIT became //go:nosplit.

// All reads and writes of g's status go through

// readgstatus, casgstatus, castogscanstatus,

// casfrom_Gscanstatus.

//go:nosplit

funcreadgstatus(gp *g) uint32 {

return atomic.Load(&gp.atomicstatus)

}

But this leads to a problem, what happens if you run out of stack with //go:nosplit?

If a function, written in Go or otherwise, uses //go:nosplit to say “I don’t want to grow the stack at this point”, the compiler still has to ensure it’s safe to run the function. Go is a memory safe language, we cannot let functions use more stack than they are allowed just because they want to avoid the overhead of the stack check. They will almost certainly corrupt the heap or another goroutine’s memory.

To do this, the compiler maintains a buffer called the redzone, a 768 byte allocation 4 at the bottom of each goroutines’ stack frame which is guaranteed to be available.

The compiler keeps track of the stack requirements of each function. When it encounters a nosplit function it accumulates that function’s stack allocation against the redzone. In this way, carefully written nosplit functions can execute safely against the redzone buffer while avoiding stack growth at inconvenient times.

This program uses nosplit to attempt to avoid stack splitting,

package main

type T [256]byte // a large stack allocated type

//go:nosplit

func A(t T) {

B(t)

}

//go:nosplit

func B(t T) {

C(t)

}

//go:nosplit

func C(t T) {

D(t)

}

//go:nosplit

//go:noinline

func D(t T) {}

func main() {

var t T

A(t)

}

But will not compile because the compiler detects the redzone would be exhausted.

# command-line-arguments

main.C: nosplit stack overflow

744 assumed on entry to main.A (nosplit)

480 after main.A (nosplit) uses 264

472 on entry to main.B (nosplit)

208 after main.B (nosplit) uses 264

200 on entry to main.C (nosplit)

-64 after main.C (nosplit) uses 264

We occasionally hit this in the -N (no optimisation) build on the dashboard as the redzone is sufficient when optimisations are on, generally inlining small functions, but when inlining is disabled, stack frames are deeper and contain more allocations which are not optimised away.

Can you use //go:nosplit in your own code?

Can you use //go:nosplit in your own functions? Yes, I just showed you that you can. But it’s probably not necessary. Small functions would benefit most from this optimisation are already good candidates for inlining, and inlining is far more effective at eliminating the overhead of function calls than //go:nosplit.

You’ll note in the example above I showed I had to use //go:noinline to disable inlining which otherwise would have detected that D() actually did nothing, so the compiler would optimise away the entire call tree.

Of all the pragmas this one is the safest to use, as it will get spotted at compile time, and should generally not affect the correctness of your program, only the performance.

//go:noinline

This leads us to inlining.

Inlining ameliorates the cost of the stack check preamble, and in fact all the overheads of a function call, by copying the code of the inlined function into its caller. It’s a small trade off of possibly increased program size against reduced runtime by avoiding the function call overhead. Inlining is the key compiler optimisation because it unlocks many other optimisations.

Inlining is most effective with small, simple, functions as they do relatively little work compared to their overhead. For large functions, inlining offers less benefit as the overhead of the function call is small compared to the time spent doing work. However, what if you don’t want a function inlined? It turned out this was the case when developing the new SSA backend, as inlining would cause the nascent compiler to crash. I’ll let Keith Randall explain.

We particularly need this feature on the SSA branch because if a function is inlined, the code contained in that function might switch from being SSA-compiled to old-compiler-compiled. Without some sort of noinline mark the SSA-specific tests might not be testing the SSA backend at all.

The decision to control what can be inlined is made by a function inside the compiler called, ishairy. Hairy statements are things like closures, for loops, range loops, select, switch, and defer. If you wanted to write a small function that you do not want to be inlined, and don’t want the to add any overhead to the function, which of those would you use? It turns out, the answer is switch.

Prior to the SSA compiler, switch {} would prevent a function being inlined, whilst also optimising to nothing, and this was used heavily in compiler test fixtures to isolate individual operations.

func f3a_ssa(x int) *int {

switch {

}

return &x

}

With the introduction of the SSA compiler, switch was no longer considered hairy as switch is logically the same as a list of if ... else if statements, so switch{} stopped being a placeholder to prevent inlining. The compiler developers debated how to represent the construct “please don’t inline this function, ever”, and settled on a new pragma, //go:noinline.

Can you use //go:noinline in your own code?

Absolutely, although I cannot think of any reason to do so off hand, save silly examples like this article.

But what about …

But wait, there are many more pragmas that Go supports that aren’t part of this set we’re discussing.

+build is implemented by the Go tool, not the compiler, to filter files passed to the compiler for build or test

//go:generate uses the same syntax as a pragma, but is only recognised by the generate tool.

package pdf // import "rsc.io/pdf"

What about the canonical import pragma added in Go 1.4, to force the go tool to refuse to compile packages not imported by their “canonical” name

//line /foo/bar.go:123

What about the //line directive that can renumber the line numbers in stack traces?

Wrapping up

Pragmas in Go have a rich history. I hope the retelling of this history has been interesting to you.

The wider arc of Go’s pragmas is they are used inside the standard library to gain a foothold to implement the runtime, including the garbage collector, in Go itself. Pragmas allowed the runtime developers to extend, the language just enough to meet the requirements of the problem. You’ll find pragmas used, sparingly, inside the standard library, although you’ll never find them listed in godoc.

Should you use these pragmas in your own programs? Possibly //go:noescape is useful when writing assembly glue, which is done quite often in the crypto packages. For the other pragmas, outside demos and presentations like this, I don’t think there is much call for using them.

But please remember, magic comments are not part of the language spec, if you use GopherJS, or llgo, or gccgo, your code will still compile, but may operate differently. So please use this advice sparingly.

Caveat emptor.