This is the text of my closing keynote from Gophercon India. It has been slightly altered for readability from my original speaking notes.

I am indebted to the organisers of Gophercon India for inviting me to speak, and to Canonical for giving me the time off to attend the conference.

If you want to see me stumble through the real thing, the video is now available.

Simplicity and collaboration

Closing Keynote, Gophercon India

21 Feb 2015

Introduction

I want to open my presentation with a proposition.

https://twitter.com/davecheney/status/539576755254611968

Being passionate about Go means being passionate about language advocacy, and a natural hazard of dwelling too long on the nature of programming results in statements like these.

But underlying the pithy form enforced by a tweet, I believe there is a gem of truth—I cannot think of a language introduced in my life time that didn’t purport to be simple. Each new language offers as a justification, and an enticement, their inherent simplicity.

On the other hand, I cannot point to a language introduced in the same time frame with the rallying call of complexity; more complexity than its contemporaries—but many instead claim to be powerful.

The idea of proposing a language which offered higher levels of inherent complexity is clearly laughable, yet this is exactly what so many contemporary languages have become; complicated, baroque, messes. A parody of the languages they sought to replace.

Clumsy syntax and non orthogonality is justified by the difficulty of capturing nuanced corner cases of the language, many of them self inflicted by years of careless feature creep.

So, every language starts out with simplicity as a goal, yet many of them fail to achieve this goal. Eventually falling back on notions of expressiveness or power of the language as justification for a failure to remain simple.

Any why is this ? Why do so many language, launched with sincere, idealistic goals, fall afoul of their own self inflicted complexity ?

One reason, one major reason, I believe, is that to be thought successful, a language should somehow include all the popular features of its predecessors.

If you would listen to language critics, they demand that any new language should push forward the boundaries of language theory.

If you would listen to language critics, they demand that any new language should push forward the boundaries of language theory.

In reality this appears to be a veiled request that your new language include all the bits they felt were important in their favourite old language, while still holding true to the promise of whatever it was that drew them to investigate your language I the first place.

I believe that this is a fundamentally incorrect view.

Why would a new language be proposed if not to address limitations of its predecessors ?

Why should a new language not aim to represent a refinement of the cornucopia of features presented in existing languages, learning from its predecessors, rather than repeating their folly.

Language design is about trade-offs; you cannot have your cake and eat it too. So I challenge the notion that every mainstream language must be a super-set of those it seeks to replace.

Simplicity

This brings me back to my tweet.

Go is a language that chooses to be simple, and it does so by choosing to not include many features that other programming languages have accustomed their users to believing are essential.

So the subtext of this thesis would be; what makes Go successful is what has been left out of the language, just as much as what has been included.

Or as Rob Pike puts it “less is exponentially more”.

Simplicity cannot be added later

When raising a new building, engineers first sink long pillars, down to the bedrock to provide a stable foundation for the structure of the building.

To not do this, to just tamp the area flat, lay a concrete slab and start construction, would leave the building vulnerable to small disturbances from changes in the local area, at risk from rising damp or subsidence due to changes in environmental conditions.

As programmers, we can recognise this as the parable of leaky abstraction. Just as tall buildings can only be successfully constructed by placing them on a firm foundation, large programs can not be successful if they are placed upon a loose covering of dirt that masks decades of accumulated debris.

You cannot add simplicity after the fact. Simplicity is only gained by taking things away.

Simplicity is not easy

Simplicity does not mean easy, but it may mean straight forward or uncomplicated.

Simplicity does not mean easy, but it may mean straight forward or uncomplicated.

Something which is simple may take a little longer, it may be a little more verbose, but it will be more comprehensible.

Putting this into the context of programming languages, a simple programming language may choose to limit the number of semantic conveniences it offers to experienced programmers to avoid alienating newcomers.

Simplicity is not a synonym for easy, nor is achieving a design which is simple an easy task.

Don’t mistake simple for crude

Just because something may be simple, don’t mistake it for crude.

Just because something may be simple, don’t mistake it for crude.

While lasers are fabulous technology used in manufacturing and medicine, a chef prefers a knife to prepare food.

Compared to the laser, a simple chefs knife may appear unsophisticated, but in truth it represents generations of knowledge in metallurgy, manufacturing and usability.

When considering a programming language, don’t mistake a lack of the latest features for a lack of sophistication.

Simplicity is a goal, not a by-product

“nothing went in [to the language], until all three of us [Ken, Robert and myself], agreed that it was a good idea.” — Rob Pike, Gophercon 2014

You should design your programs with simplicity as a goal, not aim to be pleasantly surprised when your solution happens to be simple.

As Rob Pike noted at Gophercon last year, Go was not designed by committee. The language represent a distillation of the experiences of Robert Griesemer, Ken Thompson, and himself, and only once all three were all convinced of a feature’s utility to the language was it included.

Choose simplicity over completeness

There is an exponential cost in completeness.

The 90% solution, a language that remains orthogonal while recognizing some things are not possible, verses a language attempting to offer 100% of its capabilities to every possible permutation will inherently be less complex, because as we engineers know,

The last 10% costs another 90% of the effort.

Complexity

A lack of simplicity is, of course complexity.

Complexity is friction, a force which acts against getting things done.

Complexity is debt, it robs you of capital to invest in the future.

Good programmers write simple programs

Good programmers write simple programs.

They bring their experience, their knowledge and their failures to new designs, to learn from and avoid mistakes in the future.

Simplicity, conclusion

To steal a quote from Rich Hickey

“Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication” — Leonardo da Vinci

Go is a language designed to be simple. It is a feature, not a by-product, or an accident.

This was the message that spoke to me when I first learned about the language in 2009, and is the message that has stayed with me to this day.

The desire for simplicity is woven through every aspect of the language.

My question for you, the audience: Do you want to write simple programs, or will you settle for writing powerful programs ?

Collaboration

I hope by now I have convinced you that a need for simplicity in programming languages, is self evident, so I want to move to my second topic; collaboration.

Is programming an art or a science ? Are we artists or engineers ? This one question is a debate in itself, but I hope you will humour me that as professionals, programming is a little of both; we are both software artists, and software engineers—and as engineers we work as a team.

There is more to the success of Go than just being simple, and this is the realization that for a programming language to be successful, it must coexist inside a larger environment.

A language for collaboration

Large programs are written by large teams. I don’t believe this is a controversial statement.

The inverse is also true. Large teams of programmers, by their nature, produce large code bases.

Projects with large goals will necessitate large teams, and thus their output will be commensurate.

This is the nature of our work.

Big Problems

Go is a small language, but deliberately designed as a language for large teams of programmers.

Go is a small language, but deliberately designed as a language for large teams of programmers.

Small annoyances such as a lack of warnings, a refusal to allow unused imports, or unused local variables, are all facets of choices designed to help Go work well for large teams.

This does not mean that Go is not suitable for the single developer working alone, or a small program written for a specific need, but speaks to the fact that a number of the choices within the language are aimed at the needs of growing software teams.

And if your project is successful, your team will grow, so you need to plan for it.

Programming languages as part of an environment

It may appear heretical to suggest this, as many of the metrics that we as professional software developers are judged by; lines of code written; the number of revisions committed to source control, and so on, are all accounted for character by character. Line by line. File by file.

But, writing a program, or more accurately solving a problem; delivering a solution, has little to do with the final act of entering the program into the computer.

Programs are designed, written, debugged and distributed in an environment significantly larger than one programmer’s editor.

Go recognizes this, it is a language designed to work in this larger environment, not in spite of it.

Because ultimately Go is a language for the problems that exist in today’s commercial programming, not just language theory.

Code is written to be decoded

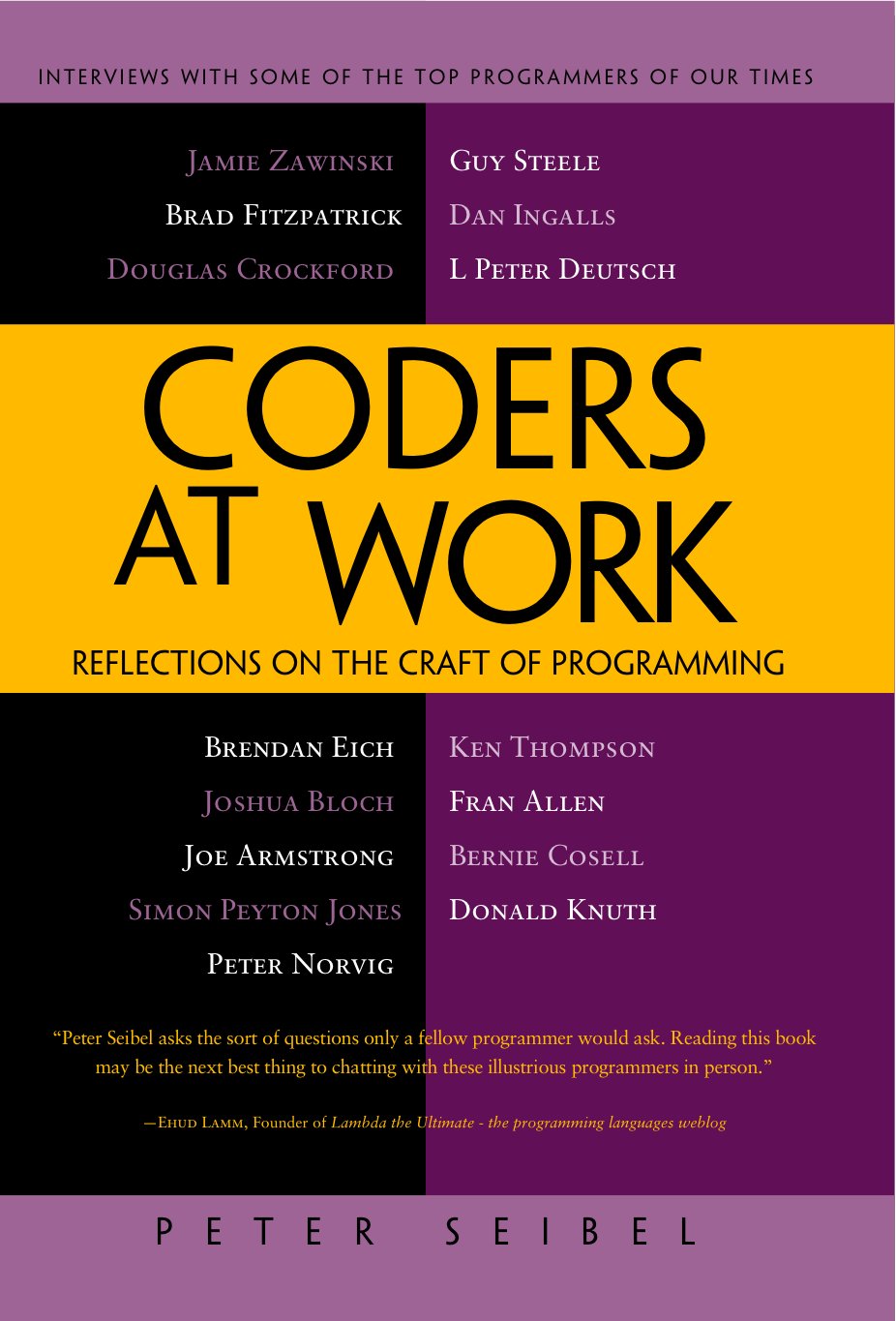

The author Peter Seibel suggests that programs are not read, but instead decoded. In hindsight this should have been obvious, after all we call it source code, not source literature.

The author Peter Seibel suggests that programs are not read, but instead decoded. In hindsight this should have been obvious, after all we call it source code, not source literature.

The source code of a program is an intermediary form, somewhere between our concept and the computer’s executable notation.

As with many transformations, this encoding of the source program is not lossless; some loss of fidelity, some ambiguity, some imprecision is present. This is why when reading source code, you must in fact decode it, to divine the original intention of the programmer.

Many of the choices relating to the way Go code is represented as source, speak to this impedance mismatch. The simplicity and regularity of the grammar, while providing few opportunities for individuality, in turn makes it easier for a new reader to decode a Go program and determine its function.

Because source code is written to be read.

How to build a Go community

Go is a language designed from the beginning to be transposed, transformed and processed at the source level. This has opened up new fields of analysis and code generation to the wider Go community. We’ve seen several examples of this demonstrated at this conference.

While these tools are impressive, I believe the regular syntax of a Go source file belies its greatest champion; go fmt.

But what is it that is so important about go fmt, and why is it important to go fmt your source code ?

Part of the reason is, of course, to avoid needless debate. Large teams will, by their nature have a wide spectrum of views on many aspects of programming, and source code formatting is the most pernicious.

Go is a language for collaboration. So, in a large team, just as in a wider community, personal choices are moderated for a harmonious society.

The outcome is that nearly all go code is go formatted by convention. Adherence to this convention is an indicator of alignment with the values of Go.

This is important because it is a social convention leading to positive reinforcement, which is far more powerful than negative reinforcement of a chafing edict from the compiler writer.

In fact, code that is not well formatted can be a first order indicator of the suitability of the package. Now, I’m not trying to say that poorly formatted code is buggy, but poorly formatted code may be an indication that the authors have not understood the design principles that underscore Go.

So while buggy code can be fixed, design issues or impedance mismatches can be much harder to address, especially after that code is integrated into your program.

Batteries included

As Go programmers we can pick up a piece of Go code written by anyone in the world and start to read it. This goes deeper than just formatting.

Go lacks heavy libraries like Boost. There are no QT base classes, no gobject. There is no pre-processor to obfuscate. Domain specific language rarely appear in Go code.

The inclusion of maps and slices in the language side steps the most basic interoperability issues integrating packages from vendors, or other parts of your company. All Go code uses these same basic building blocks; maps, slices and channels, so all Go code is accessible to a reader who is versed in the language, not some quaint organization specific dialect.

Interfaces, the UNIX way

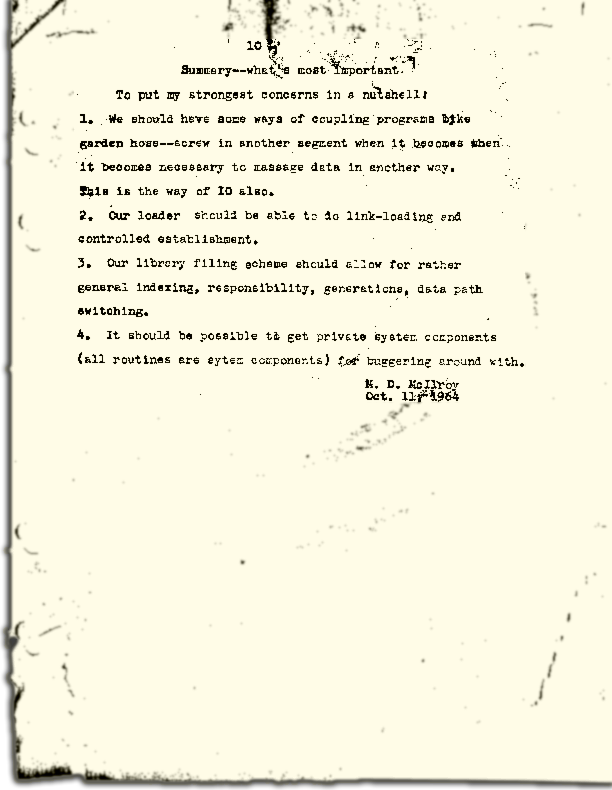

In 1964 Doug McIlroy postulated about the power of pipes for composing programs. This was five years before the first Unix was written mind you.

McIlroy’s observations became the foundation of the UNIX philosophy; small, sharp tools which can be combined to solve larger tasks, tasks which may not have even been envisioned by the original authors.

In the last few decades, I feel that programmers have lost the ability to compose programs, lost behind waves of run time dependencies, stifling frameworks, and brittle type hierarchies that degrade the ability to move quickly and experiment cheaply.

Go programs embody the spirit of the UNIX philosophy. Go packages interact with one another via interfaces. Programs are composed, just like the UNIX shell, by combining packages together.

I can use fmt.Fprintf to write formatted output to a network connection, or a zip file, or a writer which discards its input. Conversely I can create a gzip reader that consumes data from a http connection, or a string constant, or a multireader composed of several sources.

All of these permutations are possible, in McIlroy’s vision, without any of the components having the slightest bit of knowledge about the other parts of this processing chain.

Small interfaces

Interfaces in Go are therefore a unifying force; they are the means of describing behaviour. Interfaces let programmers describe what their package provides, not how it does it.

Well designed interfaces are more likely to be small interfaces; the prevailing idiom here is that interfaces contain only a single method.

Compare this to other languages like Java or C++. In those languages interfaces are generally larger, in terms of the method count required to satisfy them, and more complex because of their entanglement with the inheritance based nature of those languages.

Interfaces in Go share none of those restrictions and so are simpler, yet at the same time, are more powerful, and more composable, and critical to the narrative of collaboration, interfaces in Go are satisfied implicitly.

Any Go type, written at any time, in any package, by any programmer, can implement an interface by simply providing the methods necessary to satisfy the interface’s contract.

It follows logically that small interfaces lead to simple implementations, because it is hard to do otherwise. Leading to packages comprised of simple implementations connected by common interfaces.

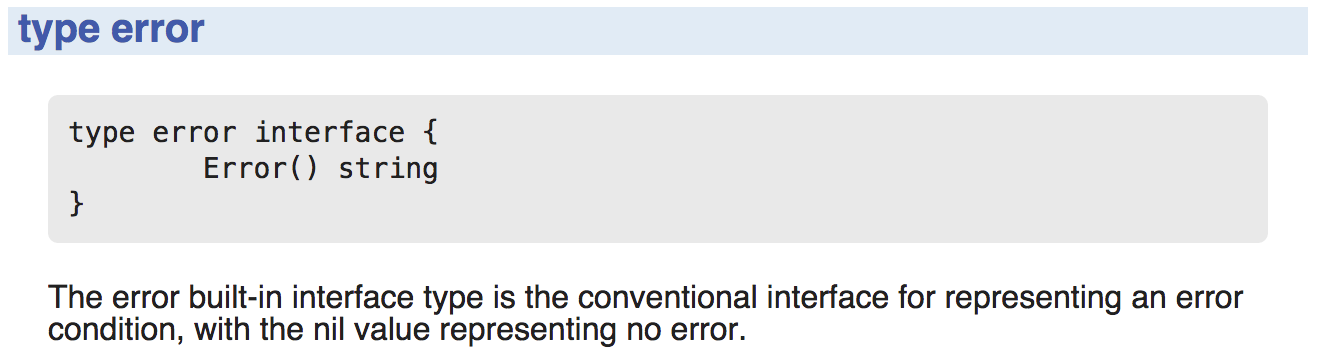

Errors and interfaces

I’ve written a lot about the subject of Go’s error handling, so I’ll restrict my comments here to errors as they relate to collaboration.

I’ve written a lot about the subject of Go’s error handling, so I’ll restrict my comments here to errors as they relate to collaboration.

The error interface is the key to Go’s composable error handling story.

If you’ve worked on some large Go projects you may have come across packages like Canonical’s errgo, which provide facilities to apply a stack trace to an error value. Perhaps the project has rolled their own implementation. Maybe you have developed something similar in house.

I want to be clear that I am remaining neutral on the relative goodness or badness of the idea of gift wrapping errors.

What I do want to highlight is even though one piece of code you integrate uses fmt.Errorf, and another a third party package, and in your package you have developed your own error handling type. From the point of view of you the programmer consuming your work, the error handling strategy always looks the same. If the error is nil, the call worked.

Compare this to the variety of error handling strategies that must be managed in other languages as programs grow through accretion of dependencies.

This is the key to a Go programmer’s ability to write an application at any size without sacrificing reliability. In the context of collaboration, it must be said that Go’s error handling strategy is the only form that makes sense.

Simple build systems

Go’s lack of Makefiles is more than a convenience.

With other programming languages, when you integrate a piece of third party code, maybe it’s something complex, like v8, or something more mundane, like a database driver from your vendor, you’re integrating that code into your program, this part is obvious, but you are also integrating their build system.

This is a far less visible, and sometimes far more intractable problem. You’ve not just introduced a dependency on that piece of code, but also a dependency on its build system, be it cmake, scons, gnu autotools, what have you.

Go simply doesn’t have this problem.

Putting aside the contentious issues of package versioning, once you have the source in your $GOPATH, integrating any piece of third party Go code into your program is just an import statement.

Go programs are built from just their source, which has everything you need to know to compile a Go program. I think this is a hugely important and equally under-appreciated part of Go’s collaboration story.

This is also the key to Go’s efficient compilation. The source indicates only those things that it depends on, and nothing else. Compiling your program will touch only the lines of source necessary.

Sans runtime

Does your heart sink when you want to try the hottest new project from Hacker News or Reddit only find it requires node.js, or some assortment of Ruby dependencies that aren’t available on your operating system ? Or you have to look up what is the correct way to install a python package this week. Is it pip, is it easy_install, does that need an egg, or are they wheels ?

I can tell you mine does.

For Go programmers dependency management remains an open wound, this is a fact, and one that I am not proud of. But for users of programs written in Go their life just got a whole lot easier; compile the program, scp it to the server, job done.

Go’s ability to produce stand alone applications; and even cross compile them directly from your workstation means that programmers are rediscovering the lost art of shipping a program, a real compiled program, the exact same one they tested, to customers.

This one fact alone has allowed Go to establish a commanding position in the container orchestration market, a market which arguably would not exist in its current form if not for Go’s deployment story.

This story also illustrates how Go’s design decisions move beyond just thinking about how the programmer and the language will interact during the development phase, and extend right through the software life-cycle to the deployment phase.

Go’s choice of a single static binary is directly influenced by Google’s experiences deploying their own large complex applications, and I believe their advice should not be dismissed lightly.

Portability

C# isn’t portable, it is joined at the hip to a Windows host.

Swift and Objective-C are in the same boat, they live in the land of Apple only programming languages. Popular ? yes, but portable ? no.

Java, Scala, Groovy, and all the rest of the languages built atop the JVM may benefit from the architecture independence of the JVM bytecode format, until you realize that Oracle is only interested in supporting the JVM on its own hardware.

Java is tone deaf to the requirements of the machine it is executing on. The JVM is too sandboxed, too divorced from the reality of the environment it is working inside.

Ruby and Python are better citizens in this regard, but are hamstrung by their clumsy deployment strategies.

In the new world of metered cloud deployments in which we find ourselves, where you pay by the hour, the difference between a slow interpreted language, and a nimble compiled Go program is stark.

Go’s fresh take on portability, without the requirement to abstract yourself away from the machine your program runs on, is like no other language available today.

A command line renaissance

For the last few decades, since the rise of interpreted languages, or virtual machine run-times, programming has been less about writing small targeted tools, and more about managing the complexity of the environment those tools are deployed into.

Slow languages, or bloated deployments encourage programmers to pile additional functionality into one application to amortize the cost of installation and set up.

I believe that we are in the early stage of a command line renaissance, a renaissance driven by the rediscovery of languages which produce compiled, self contained, programs. Go is leading this charge.

A command line renaissance which enables developers to deliver simple programs that fit together, cross platform, in a way that suites the needs of the nascent cloud automation community, and reintroduces a generation of programmers to the art of writing tools which fit together, as Doug McIlroy described, “like segments in a garden hose”.

A key part of the renaissance is Go’s deployment story. I spoke earlier and many of my fellow speakers have praised Go for its pragmatic deployment story, focusing on server side deployments, but I believe there is more to this.

Over the last year we’ve seen a number of companies shift their client side tools from interpreted languages like Ruby and Python to Go. Cloud Foundry’s tools, Github’s hub, and MongoDB’s tool suite are the ones that spring to mind.

In every case their motivations were similar; while the existing tools worked well, the support load from customers who were not able to get the tool installed correctly on their machine was huge.

Go lets you write command line applications, that in turn enables developers to leverage the UNIX philosophy; small, sharp tools that work well together.

This is a command line renaissance that has been missing for a generation.

Conclusion

https://twitter.com/supermighty/status/548897982016663552

Go is a simple language, this was not an accident.

This was a deliberate decision, executed brilliantly by experienced designers who struck a chord with pragmatic developers.

Go is a language for programmers who want to get things done

Put simply, Go is a language for programmers who want to get things done.

“I just get things done instead of talking about getting them done.” — Henry Rollins

As Andrew Gerrand noted in his fifth birthday announcement

“Go arrived as the industry underwent a tectonic shift toward cloud computing, and we were thrilled to see it quickly become an important part of that movement.” — Andrew Gerrand

Go’s success is directly attributable to the factors that motivated its designers. As Rob Pike noted in his 2012 Splash paper.

“Go is a language designed by Google to help solve Google’s problems; and Google has big problems” — Rob Pike

And it turns out that Go’s design choices are applicable to the problems that an increasing number of professional programmers face today.

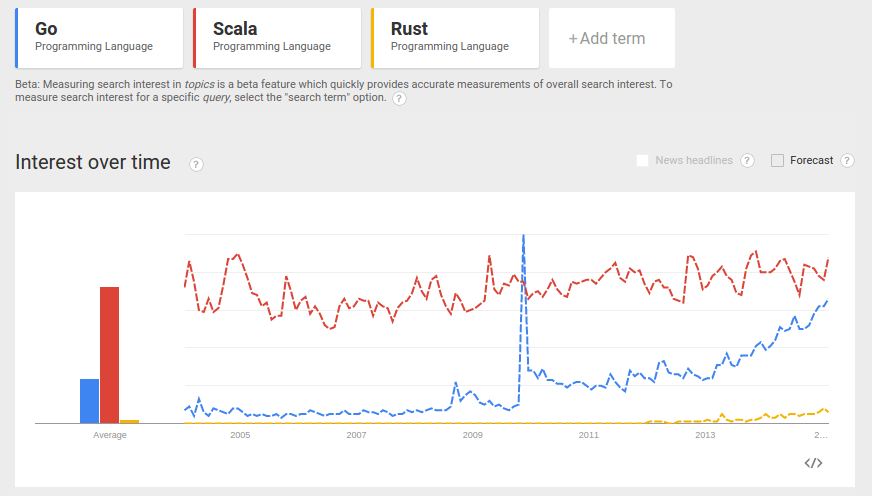

Go is growing

November last year, Go turned 5 years old as a public project.

November last year, Go turned 5 years old as a public project.

In these 5 years, less if you consider that the language only reached 1.0 in April of 2012, Go, as a language, and a proposition to programmers and development teams, has been wildly successful.

In 2014 there were five international Go conferences. In 2015 there will be seven.

Plus

- An ever growing engagement in social media; Twitter, Google plus, etc.

- An established Reddit community.

- Real time discussion communities like the #go-nuts IRC channel, or the slack gophers group.

- Go featured in mainstream tech press, established companies are shipping Go APIs for their services.

- Go training available in both professional and academic contexts.

- Over 100 Go meetups around the world.

- Sites like Damian Gryski’s Gophervids helping to disseminate the material produced by those meetups and conferences.

- Community hackathon events like GopherGala and the Go Challenge.

Lastly, look around this room and see your peers, 350 experienced programmers, who have decided in invest in Go.

In closing

This paper describes the language we have today. A language built with care and moderation. The language is what it is because of deliberate decisions that were made at every step.

This paper describes the language we have today. A language built with care and moderation. The language is what it is because of deliberate decisions that were made at every step.

Language design is about trade-offs, so learn to appreciate the care in which Go’s features were chosen and the skill in which they were combined.

While the language strives for simplicity, and is easy to learn, it does not immediately follow that the language is trivial to master.

There is a lot to love in our language, don’t be in such a hurry to dismiss it before you have explored it fully.

Learn to love the language. Really learn the language. It’ll take longer than you would think.

Learn to appreciate the choices of the designers.

Because, and I truly mean this, Go will make you a better programmer.